For years, conservatives have focused on vouchers as a way to steer state money away from public education to private schools, but now these efforts are focused on Education Savings Accounts (ESAs). Similar to school vouchers, these programs transfer public dollars to private institutions and service providers. These accounts differ from vouchers in that parents are given much more discretion, as public dollars can cover more than private school tuition. Other states have adopted these schemes and provide cautionary tales about forcing taxpayers to underwrite private school tuition and other educational costs for families, many of whom can afford to pay on their own.

What’s Moving in Louisiana Now?

Two bills (House Bill 745 and Senate Bill 313) currently moving through the state Legislature would create a new program for “Education Savings Accounts,” or ESAs, in Louisiana. The program has a three-year phase-in for student eligibility, and would allow private schools and service providers approved by the Louisiana Department of Education to accept funds from these accounts. Once established, these accounts will be filled with state dollars ranging from 55% to 160% of the state average per pupil funding amount. The range of amounts depends on three student characteristics: those who qualify to participate in the School Choice Program for Certain Students with Exceptionalities; those whose family income is 250% of the federal poverty limit, and all other students.

When fully implemented, the proposed “Louisiana Giving All True Opportunity to Rise” (LA GATOR) Program would allow the vast majority of Louisiana children to have annual access to a minimum of $5,190 per year of state money to spend on a multitude of educational or academic services. Starting in the third year of implementation, any parent can seek this account for a student as long as the parent submits an application to the Louisiana Department of Education and the parent agrees to the following in writing: to provide an education for the participating student in at least English language arts, mathematics, social students and science; to only use account funds for qualified education expenses of the student who has the account, and to comply with the all program requirements.

The bills set forth 14 different types of “qualified education expenses,” and also allow the State Board of Elementary and Secondary Education (BESE) to add other allowable expenses to the list. The bills also provide for vague and undefined “service providers” to accept funds from these accounts when these people or entities provide services to participating students.

How has this played out in other states?

Universal ESA programs do not simply move students – and their state funding allocation – from public schools to private schools. In reality, much of the demand comes from families, many affluent, who have already chosen to enroll their children in private or religious schools. Funding academic and other services for students who were never enrolled in public schools represents entirely new costs for states.

Two-thirds of students who received a private school voucher through Iowa’s ESA program in 2024 were already in private schools. Indiana, Ohio and Wisconsin all saw similar results with their ESA programs. Three-fourths of applicants in the first year of Arizona’s ESA program had never attended a public school, and nearly half came from wealthy communities. This school year’s surge in applications for Ohio’s ESA program has been so dramatic that it is nearing the total enrollment for all private schools in the state.

There may be disputes over exactly how expensive the LA GATOR program will be, but tales from other states show us the eventual cost will be significantly higher than projections. Arizona’s ESA program is projected to cost almost $900 million this school year – nearly 1,400% higher than initially projected – and is significantly contributing to a nearly $1 billion budget deficit in that state. Ohio’s ESA program is also surging past estimates and will cost nearly $1 billion this year.

The hidden costs of ESAs

Other states’ experiences with ESA programs hold a big lesson for Louisiana: The cost of an ESA program would balloon quickly in Louisiana, which has the third-highest percentage of students in private schools in the nation.

The current, average per pupil amount in the state’s funding formula is over $9,000. Further, the bill allows virtually any student to participate, with few students prohibited from the program: those who are participating concurrently with a home study program approved by the state board or a home study program registered with the department as a nonpublic school not seeking state approval; those participating in the Course Choice Program; or those participating in the School Choice Program for Certain Students with Exceptionalities.

Even for students who qualify for 55% of the average per pupil amount, it is clear how expensive this program would become. Other states have shown us that ESA programs are not cost-neutral. Most students enrolled in public schools remain in public schools, and the result is that the state ends up paying for tuition and other services which had always been borne by parents who chose private education.

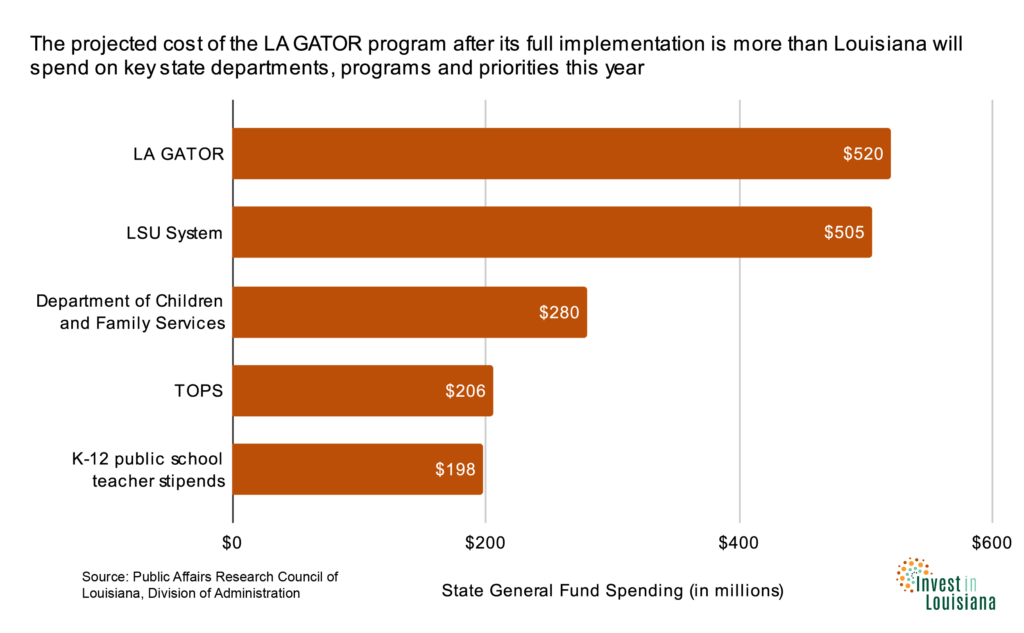

The Legislative Fiscal Office recently estimated the cost of the two proposals moving in the legislature. The LA GATOR program would cost nearly $260 million by the time of its full implementation, according to their projections. The Fiscal Office was very clear, however, that their projections were not able to account for the unknown demand from families that already have children in private schools. Another analysis from the Public Affairs Research Council, which took into account the demand from private-school students, estimated the program would cost $520 million annually after its full implementation.

No accountability for schools or families receiving public tax dollars

At full implementation, virtually all Louisiana students would be eligible to apply for LA GATOR student accounts for covered expenses. Participating private schools do not have to change their admission standards or school policies to accept all students. Public tax dollars could go to schools that openly discriminate against educators, students and families on any basis. Parents who send their children to private schools would also be forced to sign away or waive federal protections, including the guarantee for children with disabilities to receive an education.

There’s also little accountability for how families spend public tax dollars. Arizona auditors found that more than $700,000 in public funds were spent on clothing and beauty supplies. An investigation from Phoenix’s local ABC affiliate found that families spent money on luxury trips, such as ski vacations and whale-watching excursions, and extravagant appliances.

ESAs threaten public schools and larger public services

While the substantial cost of ESAs is from families who already have children in private schools, these programs still lead to students leaving public schools. The fixed costs of running a public school – paying teacher and administration salaries, performing routine maintenance and keeping lights and air conditioning working – do not decrease when taxpayer dollars “follow the child” to an unaccountable private school. This financial crunch will force districts to make tough choices on how to reduce spending, which could include less money for programs and supplies or layoffs.

Public school leaders are sounding alarm bells on the significant threat of ESAs. The superintendent of the St. Tammany Parish Public School System, one of the state’s largest and best-performing districts, recently issued a statement explaining the threat that ESAs pose to his district and others. Other district superintendents have echoed similar pushback, namely Livingston, Ouachita and other parishes.

Louisiana is facing a looming fiscal cliff, mostly due to the expiration of a temporary .45-cent sales tax, which helped dig the state out of a massive budget hole and maintain fiscal stability over the last eight years. Next year the state faces a shortfall of $559 million. That deficit is expected to grow to $733 million by the 2027-2028 fiscal year. The massive cost of the LA GATOR program will hinder Louisiana’s ability to navigate this downturn in the near-term and make it harder to make new investments in K-12 and higher education, health care and other vital programs.

A recent report from the Albert Shanker Institute found that 84% of state students are in school districts with less than adequate funding, while 57% of students are in “chronically underfunded” districts. Underfunded schools cannot flourish.

ESAs are a distraction from the problem

If implemented, ESAs in Louisiana would drain precious resources from the state coffers–resources that should be used to shore up crumbling schools and promote equity.

Louisiana does not adequately fund its public schools. The state has increased per-pupil spending just three times in more than 15 years. While Louisiana used to make annual increases to the financing formula for public schools, that policy ceased in 2008. A recent report from the Albert Shanker Institute found that 84% of state students are in school districts with less than adequate funding, while 57% of students are in “chronically underfunded” districts. Underfunded schools cannot flourish.

There is a direct link between poverty and school performance. Schools in higher-income areas perform better than those in low-income areas. In Louisiana – a state with the second-highest poverty rate and third-highest child poverty rate in the nation – 71% of all public school students are economically disadvantaged and, as a result, more likely to attend “failing” schools. Black students, who are more likely to hail from low-income families, are more than five times as likely to attend a failing school than their white counterparts.

Conclusion

Forcing taxpayers to subsidize private school tuition, regardless of a families’ income, is bad policy. It’s especially egregious considering the lack of accountability for private schools receiving public dollars. And while not all taxpayers have children in public schools, all taxpayers would be affected by the ballooning cost of the LA GATOR program. The solution to improving our public schools is to fund them more, not to take away the inadequate resources they currently have. The solution to reversing Louisiana’s endemic poverty is to use our tax dollars to make critical investments in early childhood and K-12 public education, not a costly entitlement program for private schools.