The pendulum of the criminal justice system often swings from rehabilitation-oriented policies on one end of the spectrum to punitive, tough-on-crime policies on the other. Louisiana is in the midst of such a swing.

When Gov. Jeff Landry took office in January 2024, he inherited an infamously inefficient, yet improved, criminal justice system and an impending fiscal cliff. Landry’s predecessor, John Bel Edwards, had signed sweeping reforms that aimed to reduce the nonviolent prison population and reinvest the resulting savings into services and programs that evidence has shown reduce recidivism and support crime victims.

The 2017 reforms produced more than $152 million in reinvested savings, decreased Louisiana’s prison population, while the state’s rate of nonviolent crime decreased. Still, Landry called the Legislature into a special session in February 2024, where lawmakers rolled back many of the Edwards’ administration’s reforms through the passage of “tough on crime” legislation.

The special session was followed by a regular session where legislators resisted proposals to strengthen familial ties and enhance reentry for incarcerated persons in favor of providing more funding for additional adult and juvenile correctional facilities.

Research and evidence indicate that the harsher sentences and “truth in sentencing” policies will result in a higher prison population and increased cost to corrections, with little to no effect on the crime rate.

What’s Done is Done

Louisiana has struggled for decades with high crime rates and high incarceration rates. At its 2012 peak, the state’s incarceration rate of 870 per 100,000 residents was the highest in the nation and nearly double the national average. Moreover, more than half of the 39,986-strong prison population consisted of persons sentenced for nonviolent offenses.1

In 2017, the Legislature passed a package of 10 Justice Reinvestment Initiative (“JRI”) bills that reduced sentences for nonviolent offenders, increased the availability of probation and parole and eliminated barriers to successful re-entry. A substantial portion of the savings was reinvested into services to reduce recidivism and support crime victims.

The reforms worked. Within less than five years, Louisiana’s state prison population had declined by almost 14,000 from its peak. Most of the reduction stemmed from the nonviolent offender population decreasing from 21,014 at the end of 2012, to 9,281 by the end of 2021. Louisiana’s 2021 incarceration rate – 564 per 100,000 residents – was the lowest in decades.

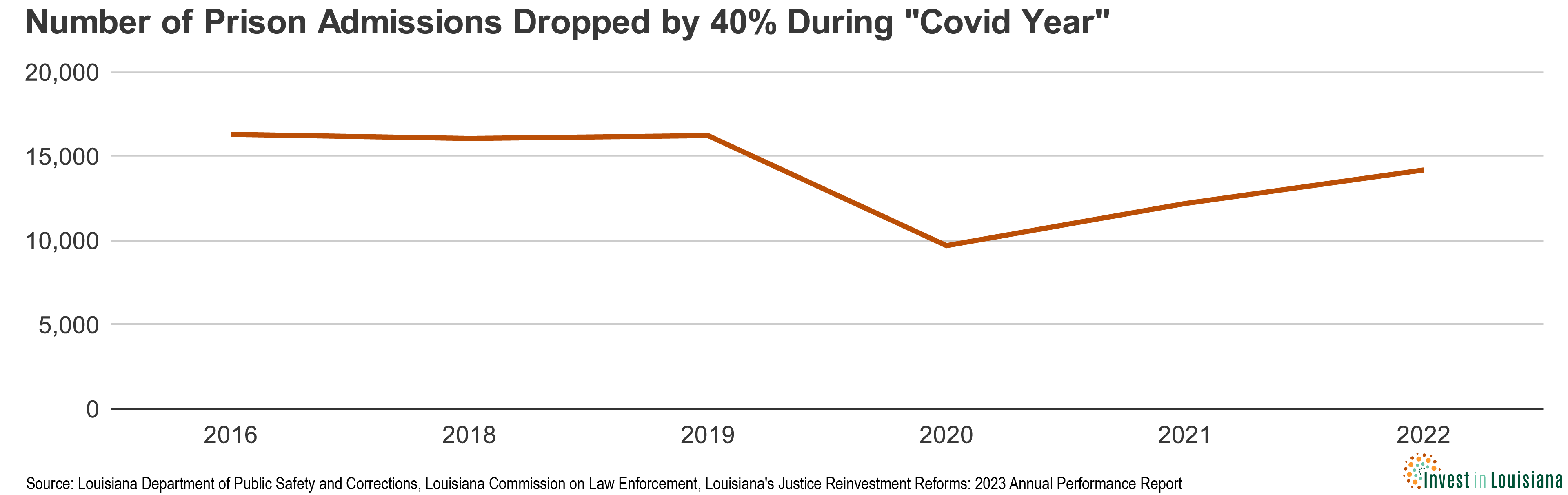

The Covid-19 pandemic also affected the prison population, as the number of people entering prison plunged in 2020. And although much of the U.S. was “back to normal” by August 2020, Louisiana’s criminal legal system took much longer to get back into stride.

As the pandemic subsided, crime spiked in Louisiana and across the country, and the JRI reforms fell out of political favor.

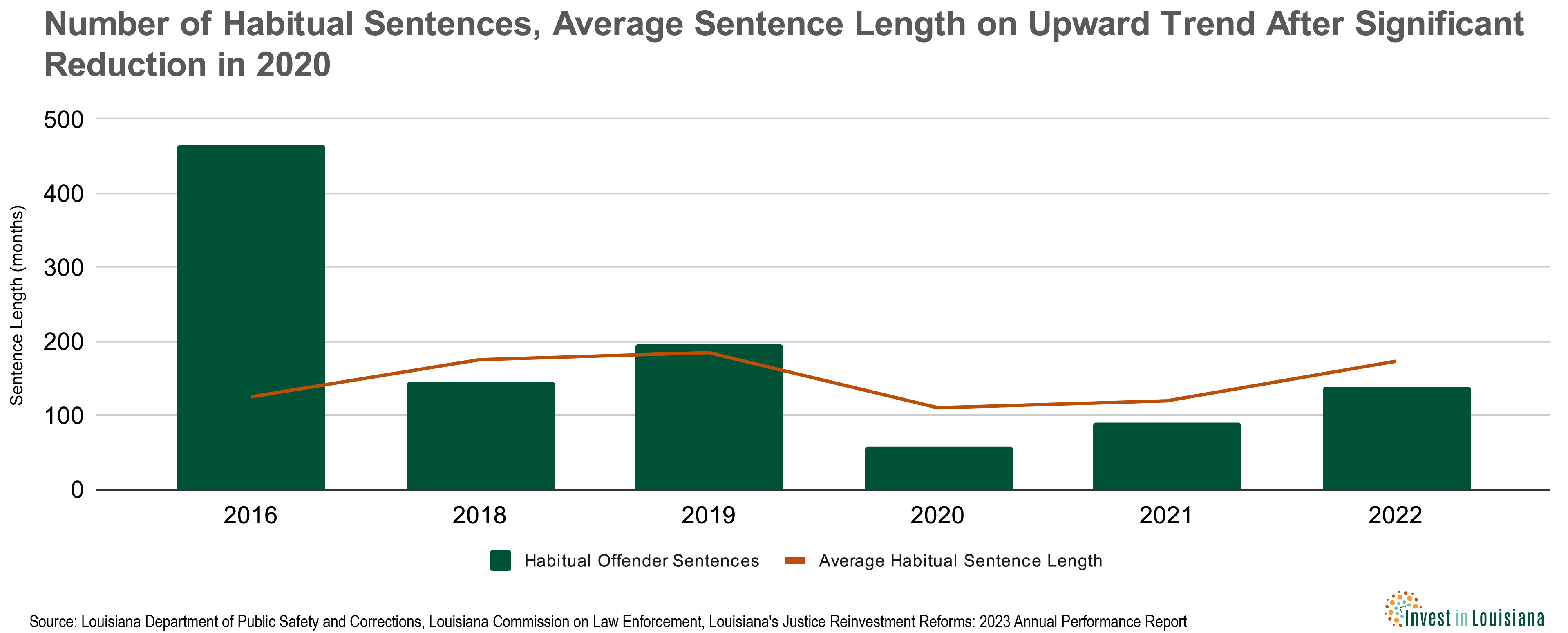

The average sentence lengths for both habitual and non-habitual offenders increased in 2021 and 2022, as did the number of habitual offender enhancements. People who previously would have been paroled were instead sent to prison, and the nonviolent prison population began increasing for the first time in five years. By 2022, Louisiana’s incarceration rate had again risen to 596 per 100,000, putting the state second behind only Mississippi’s 661 as the most incarcerated state in America.2

In addition to reducing the prison population, the JRI reforms also changed the procedures for probation and parole, which focused supervision on those people convicted of violent offenses or people with other high-risk criminal histories. As a result, the average caseload for Louisiana’s overworked probation and parole officers decreased from 140.3 cases per officer in 2016 to 90 cases per officer in 2022.3

Smaller caseloads meant officers were better able to provide the resources and services people need after leaving prison, and a lower percentage of new prison admissions were due to revocations of probation and parole. In 2016, before the JRI reforms, 51.2% of all prison admissions were due to revocations.4 This rate fluctuated over the following years, eventually dropping as low as 43.5% in 2022.5 Further, the proportion of probation and parole closures that were due to revocations of probation and parole also decreased significantly, following the same trend as prison admissions – from a high of 29.6% in 2016 to as low as 18.2% in 2020, followed by two years of slight increases that remained lower than the 2016 peak.6

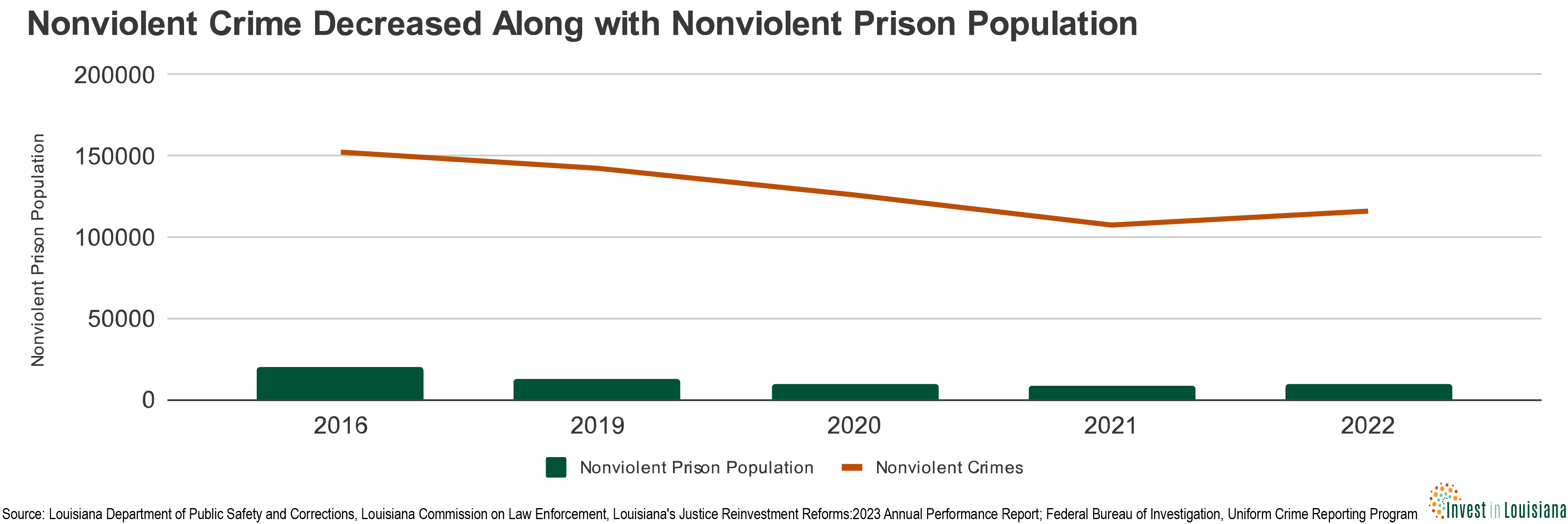

In other words, more people on probation and parole were completing the terms of their supervision, and fewer people were returning to prison for violating those terms. While this is undeniably an improvement over previous years, it remains that nearly half of all prison admissions are due to revocations,7 meaning there is still room for improvement in this area.Even though fewer people convicted of nonviolent crimes were being sent to prison, the number of nonviolent crimes continued to decrease, suggesting that the JRI reforms did not endanger the public. The number of people incarcerated for nonviolent offenses decreased by as much as 54.8% from 2016 through 2021, while the number of nonviolent crimes declined by 29.5% over the same time period.8

JRI: Savings and Successes

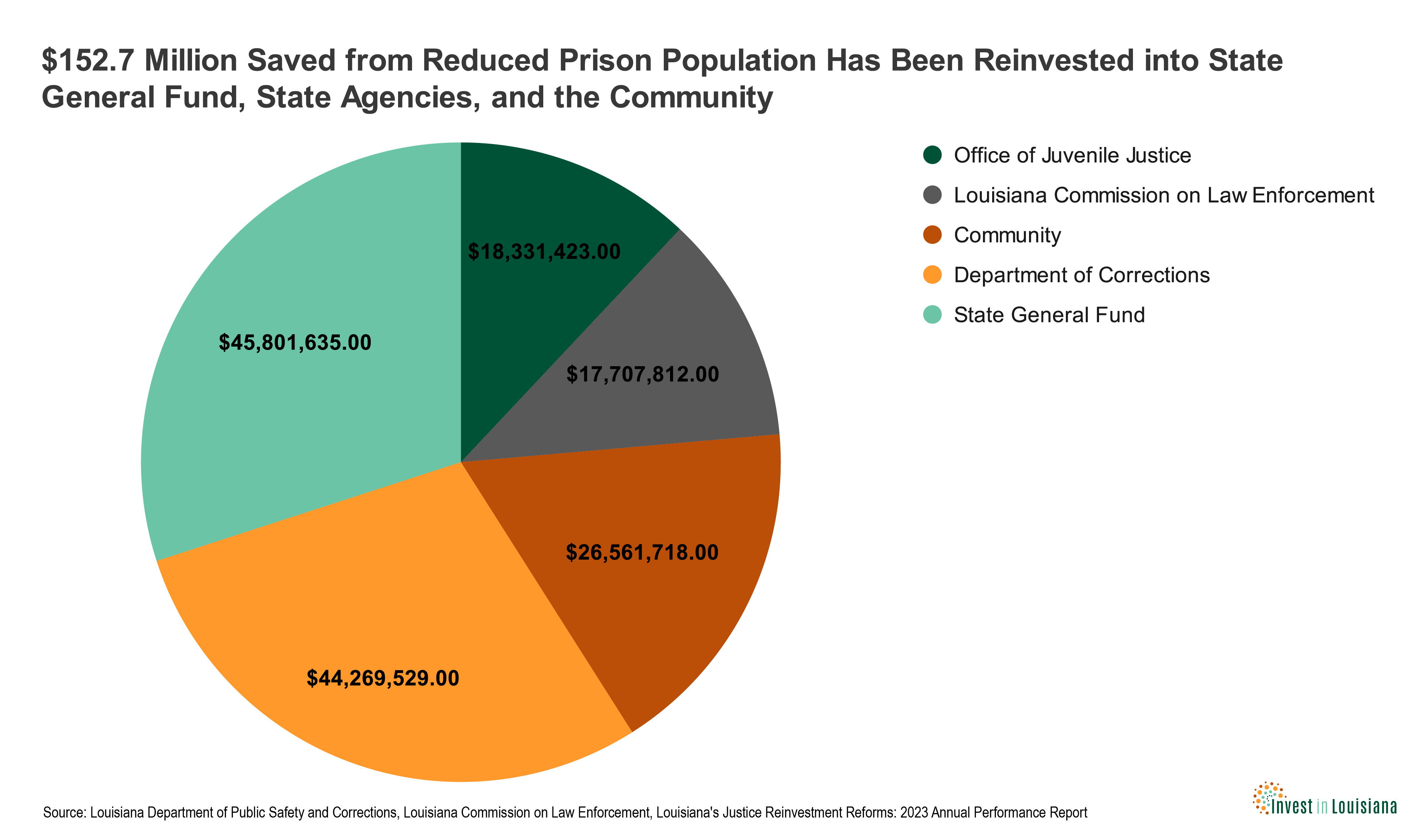

With fewer people in prison and smaller probation and parole caseloads, Louisiana realized $153 million in savings from 2017 through 2022. As the law requires, these savings were reinvested among several program areas. The Corrections Department received 30% of the savings, while community partners and organizations received 17%, and the Office of Juvenile Justice (OJJ) and the Louisiana Commission on Law Enforcement (LCLE) were each allotted 12%.9 The remaining 30% of the savings went to the State General Fund for funding state services across all agencies.

The Department of Public Safety & Corrections invested over $41 million in programming and services that served to rehabilitate people in prisons and improve their chances at successful re-entry into the community. More specifically, the agency allocated $16.4 million to re-entry related programming, services, and staffing; $12.8 million into community corrections, including probation and parole; and $12 million into vocational and educational programming.10

The investments in re-entry programs appear to have been successful. Prior to JRI, Louisiana’s 5-year recidivism rate was 43.5%. By contrast, the 5-year recidivism rate for those people released in 2017 was 40.3%. However, these rates were lower for people released from state prisons than from local jails. Additional data is needed to determine the reason for these differing rates.

People who completed educational programming prior to release had significantly lower 5-year recidivism rates, while those who had completed transitional work programs prior to release had 5-year recidivism rates lower than the overall rate, but still higher than the state prisons and those who completed educational programming.

5-year recidivism rates (2017 releases)

| Overall | 40.3% |

| State Prisons | 35.3% |

| Local Jails | 43.3% |

| Educational Programming | 29% |

| Transitional Work Programs | 36.4% |

Community-based organizations invested their 17% share of the $152 million in savings into programs that seek to reduce the number of people returning to prison. Most of the money went to the Community Incentive Grant (CIG) Program, followed by the Emergency and Transitional Housing (ETH) Program.

The CIG Program awarded over $14.2 million to community organizations to provide pre- and post-release services designed to reduce returns to prison, enhance the quality of re-entry back to the community, and improve coordination of re-entry resources. The CIG contractors and providers either provided such services directly, or they secured the appropriate services within the community. These services include:

- education programs

- family reunification services

- housing placement

- banking access

- employment placement

- mentoring

- social service registration

- job readiness training

- civil legal services

- transportation access

- vocational training

Three-year recidivism rates for people who completed a CIG program was 18%, compared to an overall 30.3% recidivism rate after three years for people released in 2019. Even for participants who did not complete their respective programs, the recidivism rate was lower than the overall cohort at 25%. This indicates that the CIG programs were a worthwhile investment.

| (CIG) | Completions – Recidivism | Non-Completions – Recidivism |

| 1st year returns | 3% | 3.1% |

| 2nd year returns | 13.2% | 21.9% |

| 3rd year returns | 18% | 25% |

The Emergency and Transitional Housing (ETH) program received $2.3 million to provide subsidized emergency and/or transitional housing for people on parole or probation, and also helped reduce recidivism. Out of the 1,264 unique participants served by the program, only 156 (12%) returned to prison.

Meanwhile, the state sent nearly $21.6 million to the Louisiana Commission on Law Enforcement, most of which (67%) went to crime victim reparations.11 The funding for crime victim reparations helped the commission reduce several years’ worth of backlogged applications and double the number of claims paid every year.12 This increase in processed claims is at least partially due to JRI reinvestment, as JRI funding in particular has been the highest or second-highest funding source for the crime victims reparations program since 2019.13

The LCLE also awarded funding to organizations that provide shelter and therapeutic services to domestic violence victims, such as Faith House, the Family & Youth Counseling Agency, the Capital Area Family Justice Center, and the Louisiana Coalition Against Domestic Violence. Several government agencies, including various crime labs and sheriff’s offices, also received funding that was used for more efficient processing of evidence.

Special Session on Crime: Exchanging What Works for What Hurts

Despite the success of the JRI reforms, Gov. Jeff Landry called the Legislature into a special session in early 2024 to take Louisiana back to the policies that made it the world leader in incarceration. Legislators passed 22 bills that, collectively, will result in more children being tried as adults, longer prison terms with less parole eligibility, and more executions carried out through untested and inhumane methods.

With the passage of Act 13, Louisiana became one of only two states to roll back legislation that automatically included 17-year-old children in the juvenile justice system. Louisiana joins just four other states – Georgia, Wisconsin, North Carolina, and Texas – that view all 17-year-olds as adults for purposes of prosecution.14 Act 14 further requires that children aged 14 and older who commit certain offenses be committed to the Department of Corrections or, in some cases, to the custody of a secure public or private institution.

Supporters of the legislation argued that 17-year-olds in juvenile facilities caused educational disruption and increased danger for younger people in secure care. Opponents emphasized the cost and logistical difficulties that will arise from incarcerating these youth with adults, as all detained persons under the age of 18 must be “sight and sound separated” from adult detainees. This requirement is a core part of the Juvenile Justice Reform Act, and compliance is additionally required for Louisiana to receive funding from the federal Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Program.

Act 6 eliminates parole for all offenses committed on or after Aug. 1, 2024, with certain exceptions for juveniles sentenced to life, while Act 7 requires anyone who commits a felony to serve at least 85% of their sentence, greatly restricting the amount of “good time” that incarcerated persons may earn. The combined effect of these laws is that people will serve much more of their sentence incarcerated than under parole supervision.

Opponents, testifying in committee, said the laws will increase danger for prison officials as incarcerated people are deprived of any hope for early release and, consequently, any incentive to work on self-improvement and rehabilitation.

It also will put additional strain on the state budget by increasing the cost of operating prisons and jails at a time when Louisiana’s corrections system already suffers from persistent understaffing – with 482 vacant positions as of January 29, 2024.15

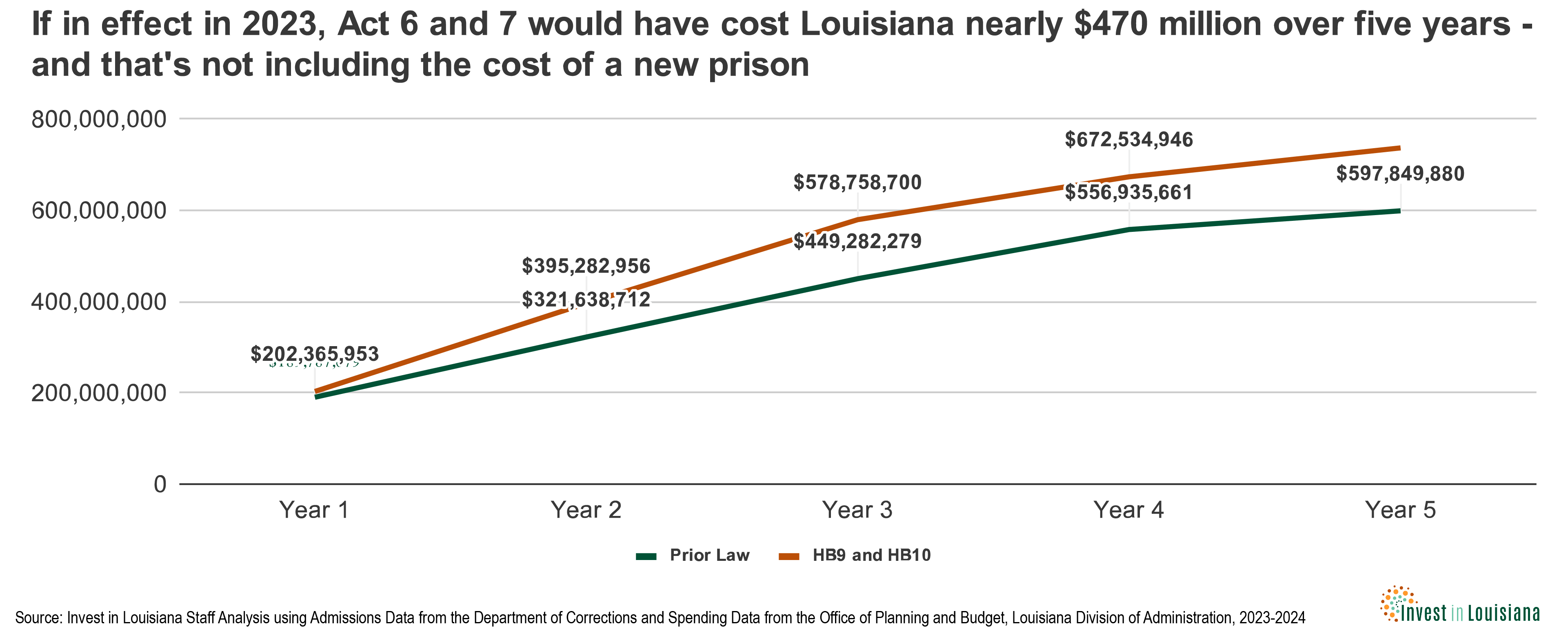

Invest in Louisiana estimates that, had Acts 6 and 7 been in effect in 2023, the state’s spending on Corrections would be about $470 million higher in the first five years.16

When incarcerated people are released to the community to serve the rest of their sentence under community supervision – parole or probation – they become less costly to the state. The per-person cost of incarceration in Louisiana is $3,167.59 per month at state facilities17 and $802.70 per month at local facilities,18 compared to the per-person cost of supervision at $183.11 per month.19 When more people spend more of their sentence incarcerated than under supervision, the total cost of corrections increases.

Investments into rehabilitative programming coincided with a reduction in 5-year recidivism rates. Assuming the approximate number of people admitted to DPSC for new felonies and their average sentence lengths remain relatively constant, it will become all but impossible to continue the reinvestments made under JRI, thereby jeopardizing the improvements that were seen in recidivism rates and programs to support victims of crime. The increased costs that result from increased prison population will also be exacerbated by lengthier sentences and increased staffing needs. The Crime and Justice Institute estimates that Act 7 will double the prison population within 10 years, creating a need for new prison construction, which the organization estimates would cost approximately $2 billion.

Legislators also approved new methods to carry out the death penalty. With Act 5, which allows the state to use electrocution and nitrogen hypoxia to carry out death sentences, Louisiana all but guaranteed it will spend millions more on litigation for people who are currently on death row and those who will be sentenced to death in the future. Because of the finality of capital punishment, those who receive this sentence are entitled to more appeals than those who do not.

A 2019 study by retired New Orleans district Chief Judge Calvin Johnson and Loyola Law Professor William Quigley found that Louisiana’s capital punishment system costs the state nearly $16 million per year. This estimate is conservative, however, as these costs do not include prosecution, or expenditures on cases that are ultimately reduced to non-capital cases, or the cost of the automatic review of capital convictions by the Louisiana Supreme Court.

Due to what death penalty opponents describe as the cruel and unusual nature of this execution method, the state will undoubtedly face contentious litigation for all future scheduled executions, which will increase the amount of money the state and its taxpayers spend on the death penalty as well as increasing the time the convicted person spends on death row.

Regular Session: Resolutions and Regressions

While Louisiana took a big step backward on criminal justice reform during the special session, there were small signs of progress during the three-month regular session that followed.

For example, legislators reduced the penalty for marijuana paraphernalia so that it is more closely aligned with the penalties for simple marijuana possession and by allowing for more than one felony expungement within a 10-year period if each felony conviction is independently eligible for expungement. Act 435 created the Back on Track Youth Pilot Program to provide at-risk youth with opportunities to participate in occupational and vocational training, life skills, healthy choices, and literacy. Act 124 specified that the individualized learning plans required for all children committed to secure care in Louisiana shall also include vocational training.

However, lawmakers failed to provide relief for people who are held in prison past their release date and refused to pass the Fairness and Safety Act for Louisiana Incarcerated Workers, which would have ensured safe working environments and more equitable pay for participants in Transitional Work Programs.

Conclusion

Ensuring public safety is a core responsibility of state government, and Louisiana taxpayers will spend $712.5 million in state general fund dollars on the Department of Public Safety & Corrections Louisiana during the 2024-25 budget year.20 Taxpayers should expect these dollars to be spent wisely, with a special focus on programs that seek to train and rehabilitate offenders rather than simply punish those who break the law.

State government has limited resources, and money the state spends to keep people locked up is money that can’t be used to educate a child, train workers, upgrade our infrastructure or provide health care and other public services to people in need. The laws passed by the Legislature in 2024 at the governor’s urging will result in more people going to prison for longer periods of time. That will drive up costs to the state, and leave fewer resources for other programs and services that help build a stronger economy.

The full budget impact of these stringent new laws won’t be felt for some time. Years will pass until the people sentenced under these new laws languish in prison instead of being paroled. But that means state officials still have time to adjust, by exploring other means of reducing crime and recidivism without imposing an insurmountable financial burden on the state.

The choice to abandon the bipartisan JRI reforms was a mistake that will put new pressure on the state budget yet is unlikely to make Louisianans any safer. But it’s not too late for Louisiana officials to mitigate the damage by investing in proven programs that help reduce recidivism by preparing incarcerated people to lead full and productive lives after release.

Footnotes

- Louisiana DOC Demographic Dashboard ↩︎

- US Department of Justice Prisoners in 2022 – Statistical Tables ↩︎

- Louisiana’s Justice Reinvestment Reforms 2023 Annual Performance Report (p. 20) ↩︎

- Louisiana’s Justice Reinvestment Reforms 2023 Annual Performance Report (p. 16)

↩︎ - Louisiana’s Justice Reinvestment Reforms 2023 Annual Performance Report (p. 16)

↩︎ - https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1iVyR3eKTWAkwZpxNI_KqbWds6Mb7PAdG (pg. 220, 221) Author’s calculation using 2023 Louisiana Violent Crime Task Force DPS&C Data Request, Louisiana Department of Public Safety and Corrections. ↩︎

- Louisiana DOC Admissions Dashboard

↩︎ - Louisiana’s Justice Reinvestment Reforms 2023 Annual Performance Report (p. 12), FBI Crime Data Explorer

↩︎ - Louisiana’s Justice Reinvestment Reforms 2022 Annual Report (pg. 25, 26)

↩︎ - Louisiana’s Justice Reinvestment Reforms 2022 Annual Report (pg. 35)

↩︎ - Louisiana Commision on Law Enforcement, Response to Public Records Request from Invest in Louisiana staff

↩︎ - State of Louisiana Crime Victims Reparations Board Annual Report, Fiscal Year 2022

↩︎ - State of Louisiana Crime Victims Reparations Board Annual Reports, Fiscal Years 2019 – 2022

↩︎ - National Conference of State Legislatures Summary Juvenile Age of Jurisdiction and Transfer to Adult Court Laws

↩︎ - Louisiana Department of Corrections Fiscal Year 2025 Executive Budget Review

↩︎ - A detailed methodology follows this report.

↩︎ - Louisiana Division of Administration 2024-25 Executive Budget Corrections Services (pg. 19, all state facilities, FY 2022-2023 actuals)

↩︎ - Louisiana Department of Corrections Fiscal Year 2024 Executive Budget Review (pg. 26)

↩︎ - Louisiana Division of Administration 2023-24 Executive Budget (pg. 139)

↩︎ - FY 25 Fiscal Highlights, Legislative Fiscal Office

↩︎

Methodology to Determine Cost Differences in Incarceration and Supervision before and after the 2024 Second Special Session (Acts 6 and 7)

To determine the cost of corrections for an average year of new felony admissions, data was extracted from the public Louisiana Department of Corrections Admissions Dashboard for the year 2023.

To calculate costs under prior law, the number of people admitted to prison on a new felony who were eligible for early release through discretionary parole or GTPS (“diminution of sentence”) and the number of people who were not eligible for either were gleaned from the Admissions Dashboard. The average length of time that someone eligible for each of these release mechanisms would spend incarcerated was also determined through the Dashboard, and the average length of time that they would spend on parole was extrapolated. These determinations were based on the assumption that people were being released at the earliest opportunity, so people who were eligible for both parole and GTPS were allocated to whichever release mechanism allowed for the earliest release. Then, to account for the housing of approximately 50% of incarcerated people at local jails, the number of people in each category was divided by two, and each half was multiplied by the yearly cost of incarceration or supervision, as applicable. The yearly costs of incarceration and supervision were added together to determine the total cost per year.

The sources for the cost amount are as follows:

- State Facilities: Office of Planning and Budget, Louisiana Division of Administration, Department of Public Safety & Corrections Supporting Document, Fiscal Year 2024-25

- Local Jails: House Fiscal Division, Louisiana Department of Corrections Budget Presentation, Fiscal Year 2023-24

- Supervision: Office of Planning and Budget, Louisiana Division of Administration, Executive Budget, 2023-2024

In these sources, cost amounts were presented as daily cost amounts. Calculations were used to determine yearly amounts by multiplying each amount by 365.

To calculate costs under new law, the number of people who would be eligible for GTPS was gleaned from the Dashboard, and the remainder were considered “Full Term Date” or “FTD.” The same steps in calculating the average time served and supervised and their respective costs were then performed.