H.R. 1, the 2025 budget reconciliation package passed by Congress and signed into law by President Donald Trump this summer, slashed funding for vital health care and food assistance programs while executing a massive shift in wealth to the nation’s richest individuals and corporations.

Buried within this harmful megabill are nominal increases in the Child Tax Credit (CTC), Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit (CDCTC) and other programs intended to defray the cost of raising children. But these increases exclude millions of children because their families don’t make enough money to qualify. By merely increasing credit amounts and reimbursement rates of these existing programs, H.R. 1 failed to address the inequities baked into each of these policies. The result is a tax structure that increasingly benefits higher-income families with children while leaving behind millions of working families who need assistance the most.

Child Tax Credit

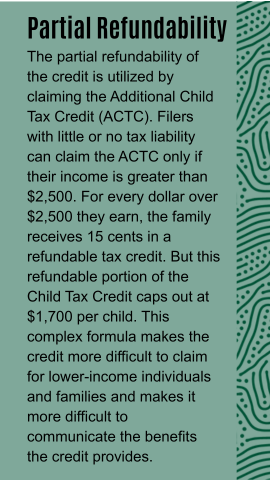

The CTC allows taxpayers to lower their federal tax liability by $2,000 per child to lighten the financial burden of raising children. H.R. 1 temporarily increases the maximum amount of the Child Tax Credit to $2,200. But it makes no changes to the credit’s refundability and earnings requirements. As a result, more than 1 in 4 children will be ineligible for the full credit because their family income is not high enough. The CTC is only partially refundable, meaning that taxpayers with little or no tax liability can receive some benefit from the policy but are unable to receive the full $2,200 credit amount.

The income needed to receive the full Child Tax Credit varies depending on parents’ filing status (married, filing jointly vs. single) and the number of children being claimed. Before H.R. 1 passed, a two-parent family with two children would have had to make $36,000 to qualify for the full credit. Under H.R. 1, that same family would need to make $41,500 to receive the full credit. Families with more children need to have higher income to qualify for the maximum credit. (Changes to the CTC structure are noted in Table 1.)

Income Needed To Receive Full Child Tax Credit

| Married, Filing Jointly | Head of Household Filers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-H.R. 1 CTC | H.R.1 CTC | Pre-H.R. 1 CTC | H.R. 1 CTC | |

| 1-child family | $33,000 | $36,500 | $25,500 | $28,700 |

| 2-child family | $36,000 | $41,500 | $28,500 | $33,700 |

| 3-child family | $39,000 | $46,500 | $34,500 | $38,700 |

| 4-child family | $45,550 | $51,500 | $42,300 | $45,800 |

| Source: Center on Poverty and Social Policy | ||||

This structure leaves behind 19 million children whose working parents do not earn enough money to receive the full credit amount – 28% of all U.S. children under age 17. In Louisiana, an estimated 43% of children will be ineligible for the full CTC because their family income is too low (Collyer et al. 2025).

And H.R. 1 tightened the eligibility for the credit, requiring that at least one parent have a work authorized Social Security number. This change would block an estimated 4.5 million children with U.S. citizenship or lawful status – including 23,000 children in Louisiana – from benefiting from the credit (Lisiecki et al. 2025). Congress’ inclusion of this provision in the legislation turns the CTC into yet another tool the Trump administration can use to harm immigrant families.

As was the case before the passage of H.R.1, the structure of the Child Tax Credit disproportionately disadvantages Black, Latino and American Indian or Alaskan Native children. These disparities are also felt across family structures, where 60% of the children of single mothers are ineligible for the full credit amount as opposed to only 14% of children in two- parent families. Similarly, families that live in rural areas (36%) are more likely to be ineligible for the full credit than those in urban areas (27%) (Collyer et al. 2025).

Child Tax Credits, at the federal or state level, work best when they are utilized as income assistance. In 2021, the American Rescue Plan Act temporarily made the CTC fully refundable, increased the credit amount to $3,600 per child and issued the credit as a monthly direct deposit to qualifying families instead of in a lump sum in filers tax return. Combined with other pandemic-era income supports, these changes transformed the financial outlook of low-income families and resulted in the single largest reduction in child poverty this century. In 2019, before the Covid-19 pandemic, the national child poverty rate as measured by the Supplemental Poverty Measure was 12.5%. With the American Rescue Plan Act’s temporary expansion of the CTC in 2021, child poverty rates plummeted to 5.2% nationwide. But those gains were immediately lost upon the expiration of the expanded CTC and the child poverty rate climbed back to 12.4% in 2022 (Louisiana Budget Project 2023).

Child and Dependent Care Credit

H.R. 1 includes the first permanent increase in the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit since 2001. This credit allows working parents with children under age 13 for the entire year to reduce their federal tax liability by claiming a percentage of their child care expenses. The credit also applies to taxpayers who pay to care for a spouse or other dependent that is disabled or otherwise incapable of caring for themselves (Boyle, Crandall-Hollick, and McDermott 2021).

The legislation increases both the maximum amount and the reimbursement rate of the CDCTC for tax filers across the income spectrum. (Changes to the CTC structure are noted in Table 2.)

| Details | Previously | The New Law | The Difference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Your family’s income (married filing jointly): | Percentage of your claimed expense: | Maximum credit for two children: | Percentage of your claimed expense: | Maximum credit for two children | This is a potential increase of … |

| $33-35K | 25% | $1,500 | 40% | $2,400 | $900 |

| $43-$150K | 20% | $1,200 | 35% | $2,100 | $900 |

| $182-$186K | 20% | $1,200 | 26% | $1,560 | $900 |

| $206K + above | 20% | $1,200 | 20% | $1,200 | SAME |

| Source: First Five Years Fund | |||||

The CDCTC is non-refundable, so lower-income families will see a reduced benefit. This credit structure, combined with strict eligibility requirements, extensive rules around tracking work-related expenses and verifying child care providers, make this credit difficult to claim. In tax year 2018, only 12% of tax filers with children claimed the CDCTC – and 44% of those claims come from households with an adjusted gross income over $100,000. Like so many aspects of federal tax policy, this credit neglects the unpaid labor of stay-at-home parents and “free” child care provided by relatives that ultimately costs the caretaker opportunities in the workforce.

Who Receives the CDCTC and Who Benefits the Most

| Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) | % of All Returns | % Claiming CDCTC | % of CDCTC Dollars | Average Credit Amount |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| $0-under $15K | 21.20% | 0.30% | 0.10% | $124 |

| $15K-under $25K | 12.90% | 5.30% | 3.10% | $347 |

| $25K-under $50K | 23.70% | 22.30% | 23.70% | $623 |

| $50K-under $75K | 14.00% | 15.20% | 15.10% | $583 |

| $75K-under $100K | 8.90% | 13.20% | 13.80% | $613 |

| $100K-under $200K | 13.80% | 30.20% | 31.10% | $603 |

| $200K-under $500K | 4.50% | 11.60% | 11.10% | $564 |

| $500K+ | 1.10% | 1.90% | 2.00% | $611 |

| Source: Congress.gov |

In 2021, the American Rescue Plan Act temporarily expanded the CDCTC by making the credit fully refundable, increasing the amount of expenses that could be claimed and credited a larger percentage of those expenses. The expansion worked hand-in-hand with the enhancement of the Child Tax Credit.

Dependent Care Assistance Program (DCAP)

H.R. 1 increases, from $5,000 to $7,500, the maximum amount of pre-tax income working parents can set aside for child care in dedicated flexible spending accounts. This provision may provide some benefit to middle- and upper-income families, but does little for low-income families whose tax liability is not high enough to utilize these increased tax deductions. Further, low-income families and people living paycheck to paycheck have less opportunity to set aside money for childcare.

H.R. 1 Changes to DCAP

| Details | Previously | The New Law |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-tax amount a household can exclude from wages to use on child care expenses through an employer offered flexible spending account | $5,000 | $7,500 |

| Source: First Five Years Fund |

Employer Provided Child Care Credit (45F)

Previously, federal tax law provided businesses that provided child care benefits for their employees a 25% tax credit for qualified child care expenses, with the credit topping out at $150,000 annually. Businesses had to spend $600,000 a year to claim the full credit amount. H.R. 1 expands these Employer Provided Child Care Credits – increasing both the percentage of child care expenses covered and the maximum credit amount. Under the new law, larger businesses would receive a credit amounting to 40% of the child care expenses they cover, maxing out at $500,000. Small businesses would receive a credit amounting to 50% of the child care expenses they provide, maxing out at $600,000.

H.R. 1 Changes to Employer Provided Child Care Credits (45F)

| Details | Previously | The New Law |

|---|---|---|

| % of child care expenses covered | 25% | 40% for larger businesses |

| Maximum Credit | $150,000 | $500,000 for larger businesses $600,000 for small businesses |

| Allows small businesses to pool resources to contract with a qualified child care provider | No | Yes |

| Source: First Five Years Fund |

The downside: Employer-provided child care remains exceedingly rare across the country, and far less accessible for part-time and low-wage workers. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 15% of workers in full-time positions have access to employer-provided child care benefits. But those benefits are only available to 7% of part-time workers. And high-wage workers are far more likely to have access to these workplace benefits. Employer-provided child care is available to 24% of top-quartile earners in the United States, while only 7% of bottom-quartile earners enjoy that same benefit.

Conclusion

Tax credits are one of the most effective policy tools available to help low-income working families pay the bills and put children on paths to a brighter future. H.R. 1 represents a profound missed opportunity to invest in the nation’s working families. Its modest increases to existing tax credits for working families do little to offset the legislation’s devastating cuts to the social safety net programs upon which low-income families rely. It reinforces a policy framework that prioritizes tax breaks for corporations and the wealthy at the expense of millions of parents struggling to make ends meet. By refusing to make the Child Tax Credit fully refundable and by tightening eligibility rules that exclude immigrant families, Congress has chosen to perpetuate a tax system that rewards privilege and punishes poverty.

The changes to the Child and Dependent Care Credit, Dependent Care Assistance Program, and Employer Provided Child Care Credits will mainly help households that already enjoy stable employment and higher wages, while leaving the poorest children with little or nothing. American families would be better served if the federal government devoted more resources to universally available income supports for families with children, instead of routing credits through employers. An ideal tax credit system should not tie the wellbeing of children to workforce participation.

Congress does not have to look far for a better alternative. When policymakers made the Child Tax Credit fully refundable in 2021, child poverty was nearly cut in half. And for the first time in the quarter-century history of the CTC, the full credit made it to the people who needed it the most. Families used that support to pay rent, keep food on the table, and pay for the child care they needed to remain in the workforce (Zippel 2021).

True support for working families means building policies that recognize the realities of low-wage work, the rising cost of care, and the structural inequities that disproportionately impact Black, Latino, Indigenous, and rural communities. Congress must do more than raise credit amounts on paper – it must guarantee that every child has access to the full benefit of these programs.

Building a fairer economy and a stronger future for America’s children starts with making sure all children have their basic needs met. Policymakers should reject the inequities cemented in H.R. 1 and fight for refundable, inclusive, and accessible family tax credits that put children at the center of our nation’s budget priorities.

References

Boyle, Conor F., Margot L. Crandall-Hollick, and Brendan McDermott. 2021. “Child and Dependent Care Tax Benefits: How They Work and Who Receives Them.” 12. Congress.gov. https://www.congress.gov/crs_external_products/R/PDF/R44993/R44993.12.pdf.

Collyer, Sophie, Christopher Yera, Megan Curran, David Harris, and Christopher Wimer. 2025. “Children Left Behind by the H.R. 1 “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” Child Tax Credit.” Center on Poverty and Social Policy. https://povertycenter.columbia.edu/sites/povertycenter.columbia.edu/files/content/Publications/Children-Left-Behind-OBBBA-Child-Tax-Credit-CPSP-2025.pdf.

Lisiecki, Matthew, Danielle Wilson, Dolores Acevedo-Garcia, Sophie Collyer, Megan Curran, Joe Hughes, Emma Sifre, and Christopher Warner. 2025. “New Estimates of the Number of United States Citizen and Legal Permanent Resident Children Who May Lose Eligibility for the Child Tax Credit.” Center for Migration Studies. https://cmsny.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/New-Estimates-of-the-Number-of-United-States-Citizen-and-Legal-Permanent-Resident-Children-who-may-Lose-Eligibility-for-the-Child-Tax-Credit-.pdf.

Louisiana Budget Project. 2023. “Census 2022: Poverty, Income and Health Insurance in Louisiana.” https://www.labudget.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Census-2022-2023.pdf.

McDermott, Brendan. 2025. “The Child Tax Credit: How It Works and Who Receives It.” 30. Congress.gov. https://www.congress.gov/crs_external_products/R/PDF/R41873/R41873.30.pdf.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2025. “Percentage of civilian workers with access to quality-of-life benefits by worker characteristic.” https://www.bls.gov/charts/employee-benefits/percent-access-quality-of-life-benefits-by-worker-characteristic.htm.

Zippel, Claire. 2021. “9 in 10 Families With Low Incomes Are Using Child Tax Credits to Pay for Necessities, Education.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/blog/9-in-10-families-with-low-incomes-are-using-child-tax-credits-to-pay-for-necessities-education.