A pair of bills would move vital public benefits into Louisiana’s workforce system—treating hunger as a labor issue instead of a human need

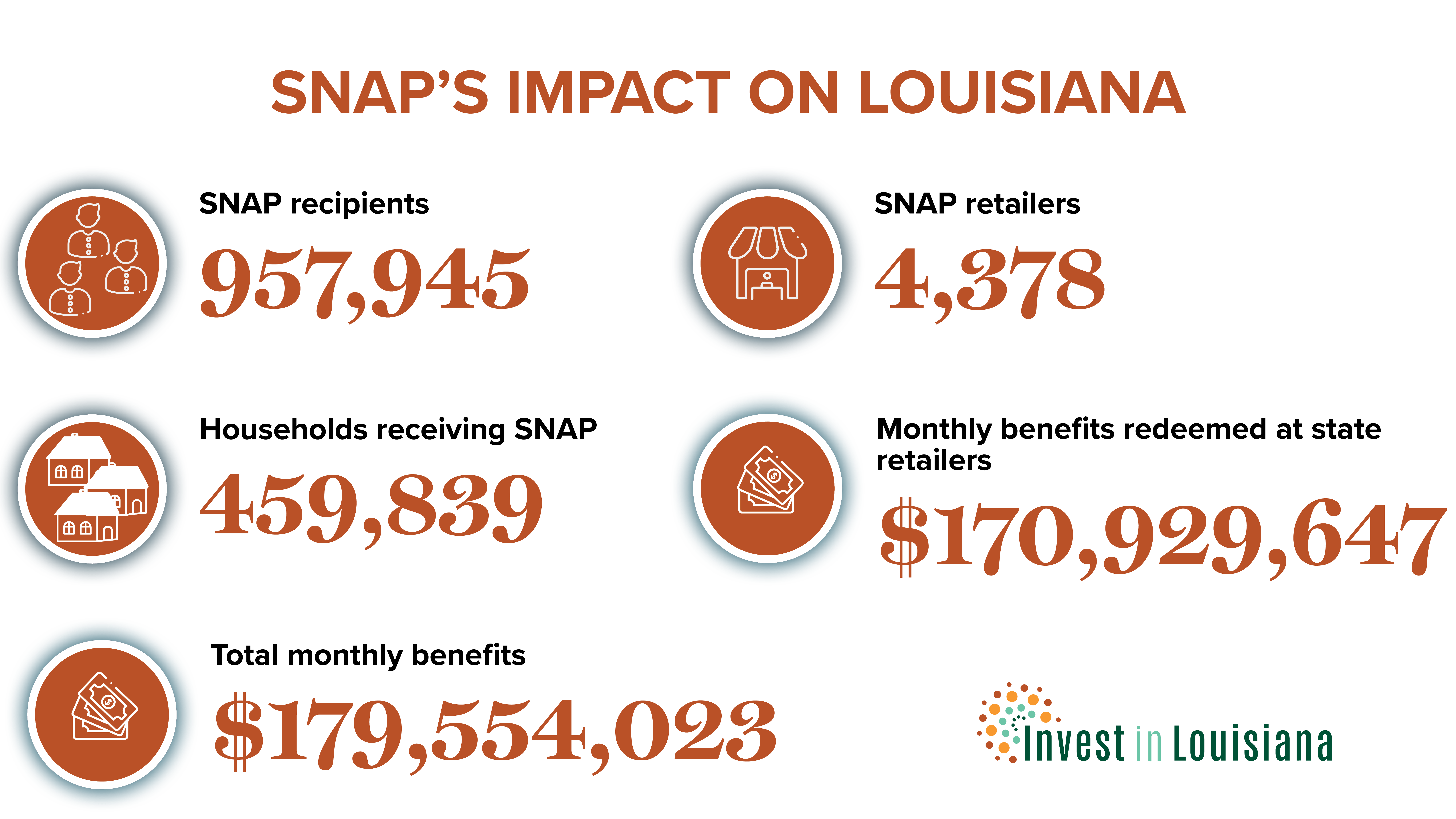

Two bills moving through the Louisiana Legislature would make sweeping changes to how our state administers key public benefits—especially the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which helps close to 900,000 Louisianans afford groceries each month. House Bill 617 by Rep. Kim Carver would restructure the Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS), removing its authority over programs like SNAP and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). House Bill 624 by Rep. Stephanie Berault would transfer these programs to the state labor department – which would be called Louisiana Works—and embed the renamed agency within a broader workforce development system.

The bills have the laudable goals of streamlining access to services and helping people achieve “self-sufficiency” through employment. But these bills reflect a national effort by conservative policy groups to redefine public benefits as tools to move people into the labor market, rather than programs that meet basic human needs. In practice, this restructuring would create unnecessary disruption, increase stigma, and undermine the core purpose of programs like SNAP.

SNAP Is About Hunger—Not Hiring

SNAP is a federal anti-hunger program. It helps low-income families buy food, supports children’s health and development, and stabilizes households during periods of hardship. Though it includes job-search and work requirements for some participants, it is not a workforce training program—and most of the people it serves are not job-seekers.

More than two-thirds of Louisiana SNAP participants are children, older adults, or people with disabilities. In fact, less than 15% of Louisianans on SNAP are adults aged 18-49 without disabilities in childless households. Many working-age recipients are already employed but still earn too little to cover basic expenses. Framing SNAP as a stepping stone to the workforce ignores both the purpose of the program, and the realities of Louisiana’s low-wage labor market.

Structural Barriers, Not Personal Failures

The push to reframe public assistance work requirements as a path to “self-sufficiency” suggests that people living in poverty lack motivation or discipline. In reality, the barriers to stable work are structural, and rooted in low wages and lack of access to affordable childcare:

- Despite decades of advocacy, Louisiana has no state minimum wage, and many full-time jobs still leave families below the poverty line. Without a baseline wage standard, even consistent employment often isn’t enough to meet basic needs.

- Job opportunities—and job quality—vary widely across the state. As of March 2025, the parish unemployment rates ranged from 3.6% in Ascension to 13.2% in East Carroll. Indeed, the unemployment rate lags far above the state average in all of the parishes which border East Carroll in northwestern Louisiana. Higher-wage, benefit-rich jobs are often concentrated in specific industries and metro areas, while rural communities frequently face a glut of low-paying or unstable positions. On average, a worker in the Hammond metro area earns $694/week, while a worker in the Baton Rouge metro area averages $1,214–nearly double.

- Poor access to childcare, transportation, and healthcare makes it difficult for people to find and keep work—especially steady, well-paying jobs. In many parts of Louisiana, affordable childcare is either unavailable or has long waitlists, forcing parents to choose between work and caregiving. Unreliable public transportation or long distances between home and job sites pose additional hurdles, particularly in rural areas. Limited access to healthcare—including mental health and reproductive care—can make it harder to maintain consistent employment. On top of that, Louisiana has no guaranteed paid family leave, meaning workers who need time off to care for a sick child, recover from childbirth, or handle a family emergency risk losing income—or even their job.

- Racial and gender discrimination continue to limit employment opportunities—especially for Black women, who face compounded barriers due to the intersection of racism and sexism. In Louisiana, Black women working full-time, year-round are paid just 49.6 cents for every dollar earned by white, non-Hispanic men, representing a wage gap of over 50% (IWPR, 2024).

The assumption behind HB 617 and HB 624 seems to be that what’s holding people back is a lack of direction or motivation—that a better case manager is all that stands between a family and stability. But for people facing generational poverty and systemic barriers, that narrative is not just misleading—it’s offensive. The people most affected by these policies are not “dependent” —they are navigating impossible systems every day with resilience and determination. A government benefit of $3 per meal will not discourage anyone from seeking meaningful work.

House Bill 624 proposes a new mandatory education and training pilot program for “able-bodied adults without dependents” (ABAWDs), to be launched in a single parish. But this population is already subject to strict federal time limits and work-reporting requirements—requirements that Louisiana chose to fully implement just last year with the passage of Act No. 308 (2024). That law blocked the state from using federal waivers that offer flexibility to states in times of economic hardship, when jobs are harder to find. Now, HB 624 proposes to layer a new, experimental pilot—complete with more paperwork, more tracking, and more red tape—on top of that already rigid system. Rather than helping people find jobs, this approach risks creating more confusion, more bureaucratic mistakes, and more wrongful terminations of food assistance.

Disruption Without Justification

House Bill 617 removes DCFS’s authority over public assistance, while HB 624 consolidates SNAP, TANF, and some disability services under the Louisiana Works agency. That transition would require new systems, staff restructuring, and massive administrative coordination—all while state agencies are already adapting to federal changes.

A coordinated system that truly makes it easier for families to get help—with streamlined applications, shared data systems, and well-supported caseworkers—is something Invest in Louisiana long supported. But uprooting core benefit programs in service of a narrow workforce model, without clear implementation plans or safeguards, is both risky and unnecessary.

If the goal is to improve access, the Legislature should invest in modernized technology, increased staffing, and simplified application processes—not force agency realignments that could delay or disrupt benefits.

Implementing this reorganization also means navigating a legal thicket of overlapping state and federal regulations that govern benefit eligibility, funding, and administration—raising the risk of missteps that could delay benefits, reduce access, or expose the state to litigation. It also throws all of Louisiana’s current workforce structure into flux.

While HB 617 and HB 624 do not explicitly eliminate Louisiana’s regional workforce development boards, they appear to position the state for a future shift toward more centralized control over workforce and social service delivery—potentially reducing the authority of local and regional entities in the process. The planned restructuring also includes a requirement to reduce by 40 positions the current staffing at Louisiana Works through natural attrition by July 2027. The overall uncertainty of the restructuring, combined with these efforts undermining existing pillars of the workforce, will impact the entire agency, not just OWD, and could even be detrimental to the workforce services that are currently being provided by LWC staff.

Finally, the “one door” model touted by supporters is more rhetorical than real. The “one-door” policy would not cover key programs like Medicaid, federal housing vouchers, or Women, Infants and Children (WIC)—all of which are essential to a stable foundation for families. For example, WIC—one of the most effective interventions for improving maternal and infant health—continues to be siloed, despite Louisiana’s historically low enrollment and alarming health outcomes for mothers and babies. Without integration of core programs, this model risks creating the appearance of streamlining without the substance.

A Process That Left Out the Public

House Bill 617 and House Bill 624 are part of a coordinated policy agenda being advanced in several states by conservative advocacy groups. This “one door” model, which proposes consolidating public assistance and workforce programs under a single agency, emphasizes employment outcomes and administrative efficiency over the lived needs of families experiencing poverty. In Louisiana, the current bills follow directly from the work of the Louisiana Workforce and Social Services Reform Task Force, created by Executive Order JML 24-44, and reflect many of the recommendations in the task force’s 2025 final report.

While the effort is framed as streamlining services, the task force process was structured in a way that consistently overlooked the perspectives of people who actually use public benefit programs—even as some agency staff and frontline workers worked in good faith to elevate those voices. The task force included agency heads, legislators, and employer representatives—but no one representing recipients of SNAP, TANF, or disability benefits. It convened a business subcommittee, but no equivalent body focused on engaging recipients or frontline community organizations. Public meetings were held in inaccessible state buildings during business hours, without public Zoom access—though out-of-state consultants regularly appeared by Zoom to present or respond to questions.

The result is a policy agenda built from the top down. While the task force’s charge was to improve service delivery for “all Louisianans who rely on such services,” its process centered state officials and business voices, and sidelined those most affected. That disconnect is now reflected in HB 617 and HB 624—bills that reorganize essential safety-net programs around a narrow vision of workforce participation, rather than the broader goals of dignity, stability, and access.

Conclusion: Protect the Purpose of the Safety Net

Public benefits like SNAP exist to help people get through hard times—not to create better workers. These programs reflect our shared commitment to each other, and basic dignity and human rights.

Invest in Louisiana supports reforms that make it genuinely easier for people to access help. If lawmakers want to improve access, they should strengthen the systems we already have:

- Modernize applications and reduce paperwork barriers

- Fund more frontline staff to improve service and reduce delays

- Eliminate unnecessary barriers and red tape

The solution to poverty is not to stigmatize those experiencing it. Programs like SNAP are not rewards for productivity—they are lifelines. Food is not a wage. It is a right.

If these bills become law, the work isn’t over. Much of how this will function still depends on decisions that lie ahead. Advocates and communities must stay engaged to ensure the implementation reflects the needs—and protects the rights—of the people these programs are meant to serve. As these changes move forward, the insight and advocacy of public servants working inside these systems—especially those closest to the communities they serve—will be essential to ensuring that reforms stay grounded in the realities of poverty and the values of human dignity.